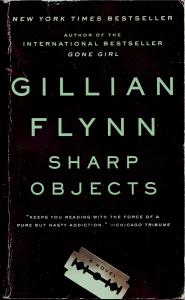

‘Domestic Noir’ is nothing new, just a rebranding of an old genre – one with which the author of Gone Girl (2012) has long been familiar: Gillian Flynn’s bestselling if less stellar debut, Sharp Objects (2006), is a stylish crime thriller too.

Psychologically fragile and hiding a shameful secret, Camille Preaker (the main female characters sport icky or ironic names, like mom Adora and half-sister Amity), is assigned under protest to cover a story about a serial killer of girls (i.e. female children, not women) in her former hometown.

Not the most original concept. So what compelled me to read on? I’m tired of genre tropes and trappings, and though its dialogue’s snappy, Flynn’s first novel isn’t as complex as her twisted breakout Gone Girl. Still, I crave the sort of subversiveness that energises both works, a transgressive tendency some feminists have condemned. Flynn’s not afraid to make women look bad. And Camille’s rich mom’s a prime suspect (at least for Detective Richard Willis, Sharp Objects’ #1 romantic interest). So to signify her wickedness, Flynn gives her a pig farm. For readers too naïve re pork and bacon production to judge Adora, Camille reports:

Even the idea of this practice I find repulsive. But the sight of it actually does something to you, makes you less human. Like watching a rape and saying nothing (p. 159).

And Camille’s 13-year-old half-sister likes to watch: ‘But that violent streak—the tantrum, the smacking of her friend, and now this ugliness. A penchant for doing and seeing nasty things (p. 161).’

Cruelty to animals goes with inhumanity, at least from an intersectional perspective. And ditto, in the small-town milieu Flynn skewers, so there’s no shortage of suspects:

Her empathy for deer doesn’t stop Camille eating steak with Richard. Yet eating meat doesn’t stop her critiquing it: ‘All those milk-fed, hog-fed, beef-fed early years. All those extra hormones we put in our livestock. We’ll be seeing toddlers with tits before long (p. 181).’ The latter could also be read as a comment on her half-sister’s precocity.

Camille’s as critical as she’s pretty. And for all her apparent fragility, she rejects paternalism, however well meant or PC on the surface. Over dinner, Richard probes for a local history of violence, and she recalls how, at a party, some boys had sex with a drunken 13-year-old. She doesn’t say that girl was herself but when Richard calls it rape, she says: “You’re sexist. I’m so sick of liberal lefty men practicing sexual discrimination under the guise of protecting women against sexual discrimination (p. 176).”

A sometimes frustratingly passive character (Flynn’s no slave to genre rules), Camille nonetheless provokes eventual resolution through her continued if ambivalent presence. In contrast to a recent domestic noir sensation, The Girl on the Train (in which active if interchangeable characters travel where the plot takes them, with routine stops at standard stations), character drives Sharp Objects’ narrative. Camille might be romantically challenged, but as a character she’s fleshed out, down to the placement of (spoiler alert) the words carved into her skin: she self-harms.

And through the course of the story, this habit reflects unflatteringly on not just her family and one of her lovers but also the culture at large. Here, as in Gone Girl, ideas appear to interest Flynn more than genre tics, and the metaphor of inscribing skin (a stock trope when killers cut their victims), adds a layer more typical of literary fiction.

Flynn’s looseness re genre conventions extends to her debut’s denouement. With the plot’s unravelling, or obligatory tying up, more or less summarised, an action revealing Camille’s state of mind assumes greater importance. Denied a happy ending, she’s left with a dawning awareness of how real care or parenting might feel.